Plastic pollution is a global challenge with adverse effects on the environment and human health. In late 2022, negotiations on a global treaty began aiming at addressing this challenge. The start of negotiations followed Resolution 5/14 of the United Nations Environment Assembly[1], which mandated member states to negotiate an international legally binding instrument to combat plastic pollution, including in the marine environment.

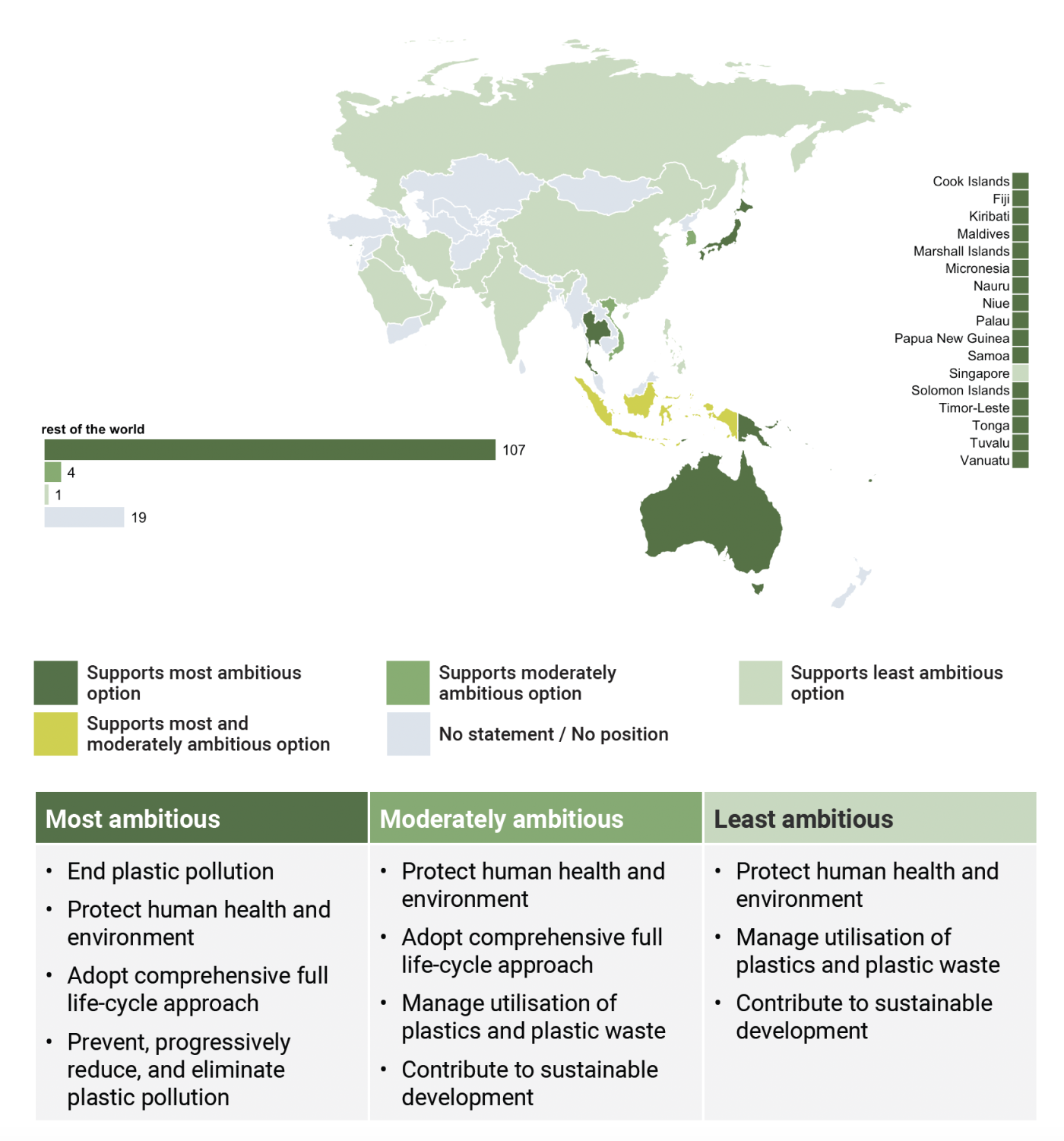

The fourth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment (INC-4), is scheduled to take place from 23 to 29 April 2024 at the Shaw Center in Ottawa, Canada. Among those attending will be a large number of delegates from countries in the Asia-Pacific region. While the decisions remain to be negotiated, many countries from the region have expressed their preferred levels of obligation and ambition in the negotiations, and have also indicated which obligations they want to reject outright. Across all treaty provisions, only half of all Asia-Pacific countries have voiced their preferences, indicating which options and levels of ambition they favour. The level of ambition is evident in the various options for individual provisions in the draft Global Plastics Treaty as shown by the new EU SWITCH-Asia analysis Positions of Asia-Pacific Countries on the Global Plastics Treaty.

In this article EU SWITCH-Asia experts have recorded and analysed the positions of all 64 Asia-Pacific countries.

Data for the analysis was collected on-site during the third session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-3), that took place from 13 to 19 November 2023 at the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Headquarters in Nairobi, Kenya. The experts took into account the positions from live statements of delegations during plenary and contact groups sessions as well as official submissions from states on the different parts of the “Zero draft text of the international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment” (UNEP/PP/INC.3/4) that was prepared by the Chair. The positions were noted and entered in a database and coded along different categories, including the ambition level of the options. The analysis covers only those core obligations in the Zero Draft where different options with clearly distinct levels of ambition could be identified.

The most ambitious options typically entail an individual legal obligation for each country to adopt policies and measures in the given issue area to reduce plastic pollution, such as by adopting standards for more sustainable plastic product design or bans on harmful plastics. They also often set legally binding targets and timeframes for each country; for example, to reach a minimum recycling rate or to phase out certain plastic products by a specified year, while also defining mandatory minimum requirements or criteria to be met by countries, such as what constitutes safe and environmentally sound management of plastic waste, or what can be qualified as sustainable product design.

The least ambitious options refrain from defining any legally binding obligations, targets, or timeframes for each country. They envision a collective commitment of countries and encourage or recommend that countries adopt policies and measures. If they include targets or deadlines at all, they leave it to each country to set its own nationally determined target or deadline, as appropriate, taking into account their national circumstances. Likewise, any provisions on requirements or criteria are usually not mandatory but serve as guidance for the voluntary efforts to be made by the countries.

The moderately ambitious options lie somewhere in between. In general, these options contain fewer legally binding elements than the most ambitious options, but more than the least ambitious options. For example, they may include a legal obligation for each country to adopt policies and measures in the given issue area but refrain from setting legally binding targets and deadlines, or defining mandatory minimum requirements or criteria.

Example: Asia-Pacific country positions on Plastic Treaty objectives

Regarding the preferences of Asia-Pacific countries, two observations can be made.

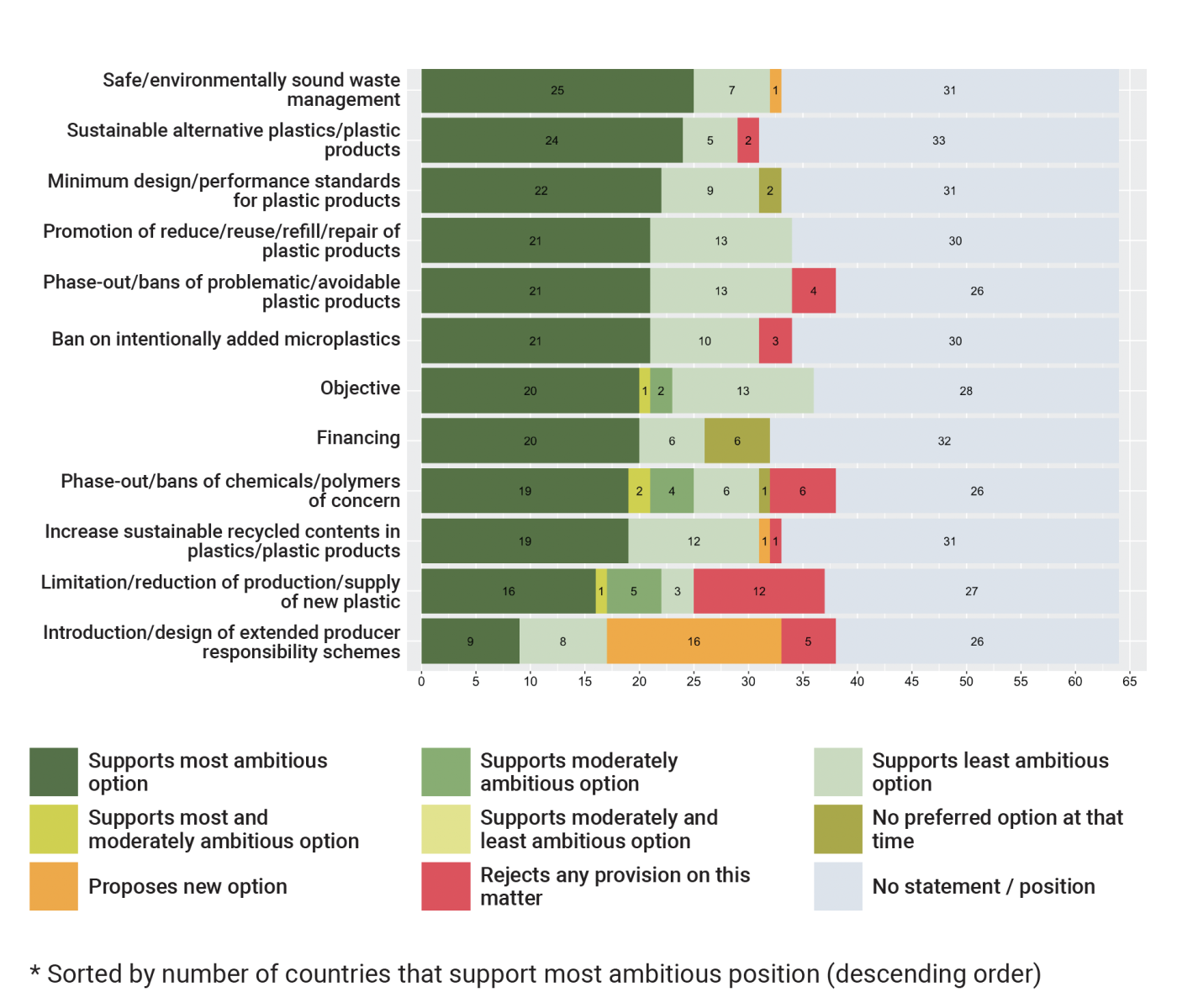

First, overall the Asia-Pacific countries tend to support the most ambitious options. For 9 of the 12 analysed treaty provisions, a clear majority – as many as 25 out of 33 countries in the Asia and Pacific region – that have stated their position are supporting the most ambitious options. The only exceptions are the treaty provisions on the limitation of the production and supply of new plastic, the reduction or even phasing-out of certain harmful chemicals and plastics, and the introduction of extended producer responsibility schemes.

Positions on treaty provisions among Asia-Pacific countries by core obligation

Second, a few Asia-Pacific countries completely reject treaty provisions in certain issue areas and do not want any international action to be taken in these areas. These include the treaty provisions on alternative plastics and plastic products, intentionally added microplastics, problematic and avoidable plastic products, use of recycled material, harmful chemicals and plastics, limitation of the production and supply of new plastic, and extended producer responsibility schemes.

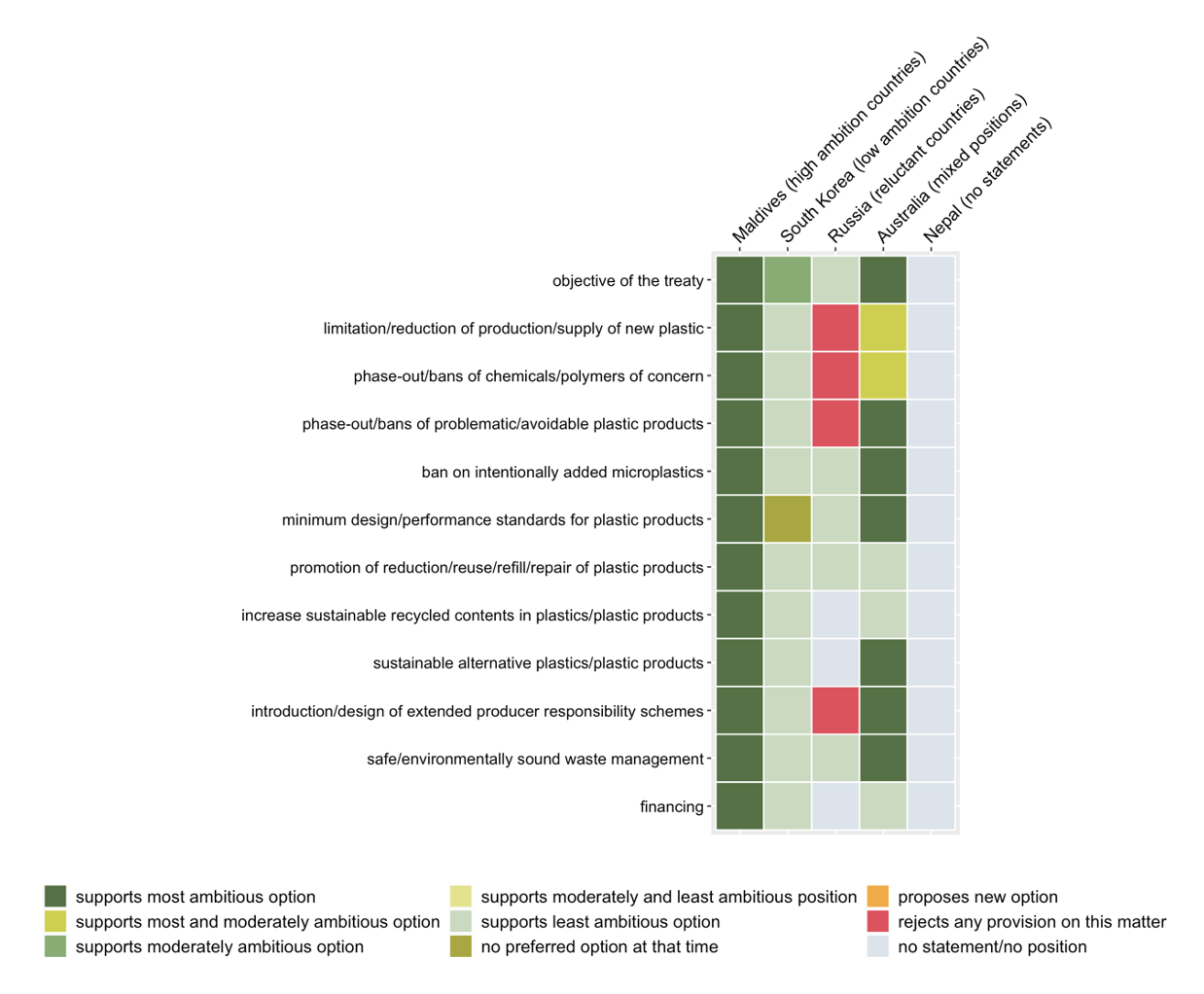

Depending on which options the countries are supporting, the countries can be sorted into three groups. High-ambition countries typically support the most ambitious options for all or almost all of the 12 selected treaty obligations. All Pacific Island States belong to this group of countries. Low-ambition countries typically support the least ambitious options of treaty obligations; Japan, South Korea, Thailand and Türkiye belong to this group of countries. Reluctant countries reject outright certain treaty obligations and do not want any international action on the respective issues, all the while supporting the least ambitious options of the treaty obligations. Bahrain, China, India, Iran, Malaysia, Qatar, Russia, and Saudi Arabia belong to this group of countries.

All other countries have either more diverse preferences, typically a mix of preferences for the least and most ambitious options of treaty obligations, like Australia, or they have not stated their positions at all, like Nepal.

Example: Asia-Pacific country statements during negotiations

Asia and Pacific country positions by core obligation of the Global Plastic Treaty

1. Management of plastic waste: Out of 64 Asia-Pacific countries, as defined by the UN, 33 have put forward a statement or position on plastic waste management. All but one support the most ambitious option: they want a legal obligation for each country to ensure safe and environmentally sound management of plastic waste, including handling, collection, transportation, storage, recycling, and final disposal. An overwhelming majority also wants the treaty to define legally binding minimum requirements for such waste management as well as minimum rates for collection, recycling, and disposal of plastic waste. Only a few countries would prefer voluntary and nationally determined minimum requirements and rates.

2. Problematic and avoidable plastic products: Thirty eight out of 64 countries from the regions have made their stance known; here the positions are more diverse. With 21 countries, the largest group supports the most ambitious option: they demand a legal obligation for each country to phase out the production, sale, distribution, import, or export of certain problematic and avoidable plastic products (to be defined), e.g. single-use or short-lived plastic products like plastic bags, cutlery, or plastic containers. They also want to set a global deadline indicating when the selected plastic products will eventually be banned. Only 13 out of the 38 countries that stated their position prefer voluntary and weaker measures. They want mere recommendations for countries to regulate and reduce plastics, and only if appropriate to phase out the production, sale, distribution, import, or export of certain plastic products; and to adopt nationally determined targets. Another four countries reject any treaty provision on problematic and avoidable plastic products.

3. Limitation of new plastic: This is where Asia-Pacific countries are most divided, falling into two opposing groups. Out of a total of 37 countries taking a position, 16 see a legal obligation and individual targets for each country to limit the production and supply of new plastic, the raw material of any plastic product. Twelve countries reject any obligation that would target the production and supply of new plastic. The nine other countries lie in between these two positions. They call for collective efforts to manage and reduce the global production and supply of new plastic, with or without nationally determined targets. They refrain, however, from demanding legally binding measures and targets for each country.

Conclusion

The Country Positions Publication reveals that while positions on the Global Plastics Treaty are diverse in the Asia-Pacific region, many countries that have stated their positions tend to support an ambitious treaty. It remains to be seen how ambitious the final treaty will be. Nevertheless, it is already clear that any treaty will have important consequences for national policymaking in the Asia and Pacific region. Depending on the already existing national policy landscape, the treaty will require significant reforms in plastic governance policies in individual Asia-Pacific countries.

Download Download